It doesn't take much exposure to scientific texts to realize that they're structured quite differently from everyday writing. Words tend to be longer; suffixes and prefixes abound; and the words themselves can be obscure, or even unknown, outside of a particular field. Over at his blog Ideas Illustrated, Mike Kinde analyzed passages from different types of English texts and quantitatively confirmed what we intuitively already know: scientific (in this case, medical) writing is strikingly different in composition from that found in literature and professional texts.

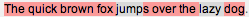

Using Douglas Harper's Online Etymology Dictionary, Kinde matched words with their linguistic origins, then wrote a script to color-code each word in a given passage with that origin and link it to its dictionary definition. The results look like this:

Using Douglas Harper's Online Etymology Dictionary, Kinde matched words with their linguistic origins, then wrote a script to color-code each word in a given passage with that origin and link it to its dictionary definition. The results look like this:

Here, the pink shading designates words that come from Old English, while the gray represents Gallo-Roman and Middle Low German origin, respectively. (The link of each word to its definition, as well a mouse-over label for its etymology, aren't reproduced here, so I strongly encourage you to check out Kinde's original post, as well as the Etymology Dictionary, for more details.)

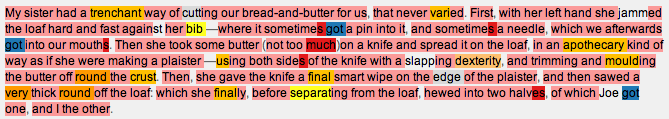

Things get a little more interesting when he increases the length and complexity of the passage, using an excerpt from Charles Dickens's Great Expectations:

Things get a little more interesting when he increases the length and complexity of the passage, using an excerpt from Charles Dickens's Great Expectations:

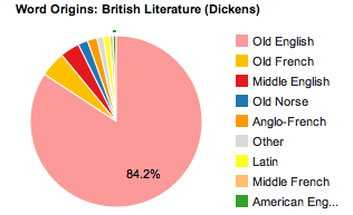

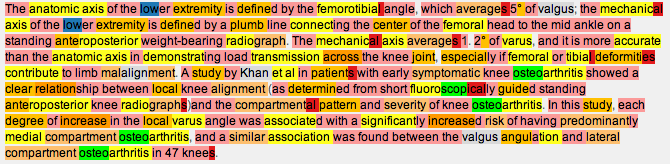

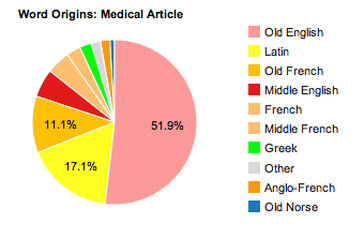

Now we have a nice mix of word origins, although Old English is still clearly the main source. Interestingly, when he analyzes a passage from Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the percentage of words derived from Old English drops to 72.9% of the total, in part due to the addition of Greek, Old Norse, Scandinavian, and Native American to the list of word origins. A legal text, describing nations' borders at sea, provides even more insight: the percentage of words derived from Old English drops to 64.4%, while Latin and Old French combine to provide nearly 20% of the total. The further away we get from everyday spoken English, the lower the percentage of Old English-sourced words appears to be, and the more a text correlates with a high level of education on the part of the author, the more frequently we find words of Latin and Greek origin. Case in point, the following excerpt from a medical text:

Barely over half of the text is made up of Old English-derived words, Latin gives us an astonishing 17.1%, and Old French comes in close behind representing 11.1% of the sample. Of course, French comes from Latin, and Kinde admits in the comments section that his selection of a category for any given word was somewhat arbitrary, choosing to simply use the first language mentioned in the Etymology Dictionary entry. Still, it's a fascinating look at just how different "the English language" can be depending on the way it's used and for whom it's intended.

At the beginning of his post, he mentions having wanted to write an app that would analyze any given text in this manner, and I can imagine spending (wasting?) hours and hours comparing different branches of science, different journals, or even publications from different research groups. It would be fascinating to see if papers written in English by a French research group, for example, tend to have a higher frequency of French-derived words than those from a German group. I know I use word cognates frequently in speaking another language, even if the meaning in the non-English language may not be exactly what I intend, only because they come to mind much more readily. Who knows what kinds of hidden linguistic patterns we might find in academic publishing?

Unfortunately, he's abandoned this idea as infeasible (for now, at least) given the amount of "manual intervention" that was required for his current analysis. A basic, much less visually-pleasing version exists over at the Etymology Discovery Message Board (though it pains me to direct traffic to a site with an its/it's mistake in the first line). Until Mike Kinde, or another like-minded programmer, can figure out how to automate his process for the masses, we'll have to be content with these analyses for a reminder of just how complicated (but interesting!) English can be.

At the beginning of his post, he mentions having wanted to write an app that would analyze any given text in this manner, and I can imagine spending (wasting?) hours and hours comparing different branches of science, different journals, or even publications from different research groups. It would be fascinating to see if papers written in English by a French research group, for example, tend to have a higher frequency of French-derived words than those from a German group. I know I use word cognates frequently in speaking another language, even if the meaning in the non-English language may not be exactly what I intend, only because they come to mind much more readily. Who knows what kinds of hidden linguistic patterns we might find in academic publishing?

Unfortunately, he's abandoned this idea as infeasible (for now, at least) given the amount of "manual intervention" that was required for his current analysis. A basic, much less visually-pleasing version exists over at the Etymology Discovery Message Board (though it pains me to direct traffic to a site with an its/it's mistake in the first line). Until Mike Kinde, or another like-minded programmer, can figure out how to automate his process for the masses, we'll have to be content with these analyses for a reminder of just how complicated (but interesting!) English can be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed